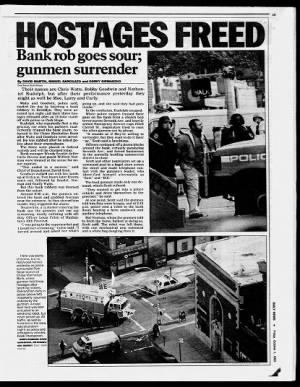

It’s August 19, 1971. Men armed with machine guns stand guard at Santa Martha Acatitla prison in Mexico City. The warden is expecting a visit from high level government officials.

A helicopter comes into view, and everything seems like business as usual. As the chopper lands in the prison yard, inmate Joel David Kaplan is ready. Within a matter of seconds, Kaplan calmly boards the craft and it lifts off without a shot being fired.

This was the first known helicopter escape in history. Kaplan, a wealthy New York businessman, was flown to Texas, where he then boarded a private jet to California. Joel’s sister, Judy, was the mastermind of the getaway. The Mexican government never initiated extradition.

Does this story sound familiar? If so, you probably remember the 1975 action movie Breakout, starring Charles Bronson and Robert Duvall. This helicopter escape story was the inspiration for that movie.

Or maybe you read the actual book of the escape, The 10-Second Jailbreak: The Helicopter Escape of Joel David Kaplan, when it was released back in 1973.

This week’s article is inspired by a “pivotal” figure in that story…the helicopter.

Bamboo Dragonflies

Around 400 BC, Chinese children played with a wooden flying toy called the “bamboo dragonfly”. This early bamboo-copter (also known as a “Chinese top”) had a simple but effective design. The stick (rotor) was rapidly spun between the hands in one direction to achieve lift. This is the genesis of the helicopter.

The Father of Flight

That simple toy inspired English engineer George Cayley to study the principles of aeronautics in the early 1800s. Known as the “Father of Aviation,” he was the first scientist to develop the concept of the modern airplane.

Cayley discovered why airplanes fly. In essence, they use the four forces of weight, lift, drag, and thrust. Cayley identified these forces, explored their interaction, and developed the concept of the cambered wing – the breakthrough discovery that made planes lift off the ground when thrust was applied.

The Wright Brothers attributed their success to Cayley’s findings. While the Wright Brothers enjoyed the glory, it was Cayley’s research that made it all possible.

The Aerial Screw

A few hundred years before Cayley, an Italian “polymath” of the High Renaissance period had conceptualized vertical flight. Any guesses who it was?

Although his claim to fame came mostly as a result of his paintings, Leonardo da Vinci was also a brilliant engineer, scientist and architect. In the 1480s he sketched out his design for a machine called the “aerial screw”.

Leonardo’s notes suggest that he built small models of it, but couldn’t figure out how to stop the rotor from making the craft spin in the opposite direction. Think of Leonardo’s design as “half-a-coptor.”

Stopping the Spinning

Torque is the force that causes things to spin. The blades on a helicopter generate lift by spinning around a vertical mast. When those blades spin, they create a “torque reaction” on the body of the craft, making it want to rotate in the opposite direction.

The solution? A small propeller on the tail of a modern helicopter counteracts this force and keeps the body stable. This was what Leonardo couldn’t figure out. His half-a-coptor would have been a dizzying experience!

Rescue 1426

While Joel Kaplan escaped by helicopter, many others have been rescued by one. The following heroic story was featured in the Washington Post. I edited for length…

Two ships (one a fully loaded oil tanker) collided in the Gulf of Mexico. Both were ablaze, one spewing flaming oil onto the ocean’s surface. Sailors were dying on the ships and in the scalding water.

Three Coast Guard airmen scrambled into an orange-and-white helicopter to attempt a rescue. They noticed that the helicopter’s radar altimeter wasn’t working, which is critical to flight safety, and it was against regulation to fly over water at night without it.

Yet these brave men took off anyway. They radioed ‘Rescue 1426’ (the tail number), to get air clearance priority. As they neared the collision site they observed a massive sea of fire. Suddenly, an explosion on the tanker shot up a massive mushroom of fire. Their helicopter jolted violently, but the pilot regained control.

Two sailors were perched on a railing at the back of the tanker. The deck was boiling hot, and they were about to jump. The helicopter crew lowered the rescue basket, but because of the ship’s overhang, they could only swing the basket toward the stranded sailors. In desperation, they both jumped, grabbed the basket, and were hoisted in. They surely would have died if they’d missed.

Then the crew flew to the other ship where a group of sailors was clustered on the ship’s bridge. They lowered the basket and several men jumped in. They pulled them up and lowered it again. As space ran low, sailors sat on one another’s laps. The pilot struggled to keep the helicopter hovering over the burning ship. The heat and turbulence stressed the transmission beyond its permitted tolerance, and could have ignited the fuel.

In the end 22 men were saved by Rescue 1426, which now hangs in the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum. This is one of many heroic stories in which lives were risked and saved because Leonardo da Vinci and George Cayley envisioned a reality that seemed impossible at the time.

The definition of “impossible” is: not able to occur, exist, or be done. This is inaccurate. It should be time based…not able to occur, exist, or be done now. In the words of Charles Swindoll:

“We are all faced with a series of great opportunities brilliantly disguised as impossible situations.”